After winning two Grammy awards in 1996, members of TLC stood in front of the post-ceremony press conference and exposed the music industry’s rotten underbelly. Chilli stepped up to the mic and said, “We’re not gonna sugarcoat things anymore. We’ve been quiet long enough.” With group members Left Eye and T-Boz dressed in all-white behind her, Chilli’s voice cut through. She explained that despite selling ten million records and being the highest-selling girl group of all time, TLC was, “broke as broke can be.” It should have been a celebratory night. But a funk hung over the affair. How could three of the generation’s most dynamic performers, at the peak of their fame, be poor, and eventually forced to file for bankruptcy?

That moment was foreshadowing. Girl groups and boy bands used to be a central feature of the pop and R&B landscape. They collapsed into nostalgia as the music industry quietly turned its back on group acts in favor of more lucrative endeavors.

Since TLC’s callout, the system only got more ruthless. Execs are obsessed with profit more than ever. Record labels have scaled back investment across the board, barely backing solo artists, let alone the more complicated, expensive group acts. We’re still having important conversations about how artists are nickeled and dimed. But groups have been shoved all the way to the margins. This is a loss for our culture.

A legendary group is greater than the sum of its parts

When groups work, it’s magical. I feel completely taken watching the personalities ricochet off one another and fuse together at the same time. I love the interplay of distinct vocal textures. Raspy, bell-clear, deep, open, nasal, agile.

Michelle’s warm tones floating beside Beyoncé's powerful and chesty belt. Kelly providing a wide foundation for the harmonies when needed or attacking the top of the chord with the force of multiple singers. The vibrato and breathing in perfect sync. When I hear it I can’t help but admire the collective discipline and artistry behind the performance.

There is something universally pleasing about seeing bodies in sync. Group choreography in particular speaks to something primal in us, the same thing that makes us stop and watch a school of fish or flock of birds travel in unison. There's beauty in coordination and what seems like a magnetic connection between the artists.

And we can’t forget the opportunities for emotional investment as a fan. We choose our favorite member, we dissect interview clips to decode the interpersonal dynamics, we learn each of their quirks and offerings. Our parasocial connections to celebrities is amplified by group lore.

The music industry started seeking profits above all

Finances partially explain the decline. Group acts are expensive to build and maintain. Labels have to invest more dollars in vocal training, outfits, hotel rooms and airplane tickets. Then there's the split. Four members means four ways to divide profits in a landscape where streaming has already collapsed margins for most artists. And in the era of streaming, where a million plays will barely cover rent, those collapsed margins matter. Most artists make their money from tours, merchandise, and brand partnerships, not music itself. And the numbers just don’t stretch easily across multiple people.

The labels operate with maximum risk aversion, finding artists who are algorithm and viral moment-ready. Groups require patience, development, and faith in something that might not monetize for years. But quarterly earnings calls don't accommodate artistic vision or cultural investment.

It’s a private equity mindset applied to human creativity: “trim the fat,” “increase efficiency,” “maximize shareholder profits.” It feels like a natural extension of the financialization of everything in the world. Hospitals, schools, clean water, decent housing and space for play have all been turned into profit-seeking ventures. So music, the thing that sustains so many of us, and group acts, the cultural phenomena that raised many of us, become prey too.

Groups require curation and more artist development

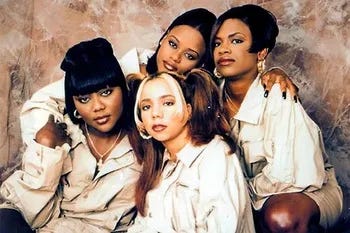

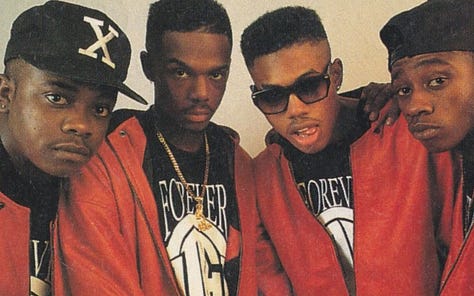

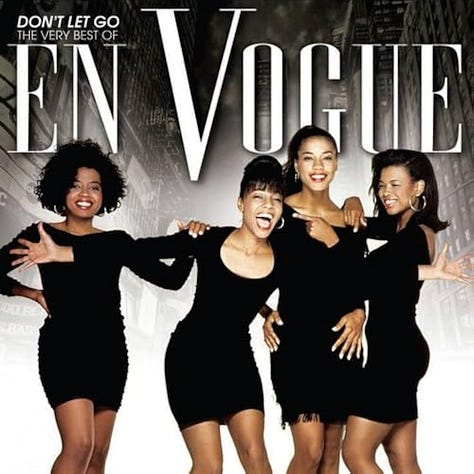

The most legendary groups weren't accidents or even organic discoveries, they were architectural productions. Controversial figures like Simon Cowell and Lou Pearlman1 understood that you find the right pieces, then teach them how to fit together. Destiny's Child, New Edition2, SWV, En Vogue, Jodeci, Backstreet Boys, NSYNC, Take That, Fifth Harmony, Little Mix and the Spice Girls all emerged from a system that believed in crafting public personas as carefully as songs. Behind the scenes you’d find managers, choreographers, vocal coaches, stylists, and storytellers who believed in a long arc, in narrative, in building something lasting. Modern A&R seems less capable or interested in continuing that legacy.

Some of the artist development techniques traced back to Berry Gordy's MoTown finishing school, where artists learned not just to sing but to carry themselves, speak to press, embody stardom. This was investment in human potential that could take years to pay off, but when it did, it created legends. Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson, Diana Ross, Gladys Knight, Lionel Richie, Smokie Robinson, and Marvin Gaye all spent time at the school.

Artist development also used to happen in a wider ecosystem. For example, the Mickey Mouse Club functioned as finishing school for more recent pop icons. Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Justin Timberlake, Ryan Gosling learned their craft in front of cameras, surrounded by child peers serious about performance, backed by adults who saw a long game. Disney and Nickelodeon continued this tradition, launching careers with years of training and infrastructure behind them: Miley Cyrus, Ariana Grande, Olivia Rodrigo, the Jonas Brothers, Keke Palmer, Zendaya, Selena Gomez, Sabrina Carpenter.

And for many, many Black artists, the church was a site for spiritual and artistic development. Black churches have essentially functioned as a music conservatory for Black children for decades. Whether one belonged to the youth choir, the praise dance team, or the regular skits and plays, the church congregation provided an early audience to test vocals, choreography, and crowd engagement. Speaking from personal experience, I learned harmonies, vocal placement, music theory, improvisation, and how to memorize an 8-count all before my teenage years. This particular site of artist development gave us Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, Brandy, and Usher. It was also the foundation for many of our great R&B group acts, whose vocal prowess was the center of their success.

These different systems, from Disney to the AME church, had some shared beliefs. That artists can be created and talent alone is insufficient. That craft and charisma can be taught. That groups matter.

Now, if you’re an emerging artist you hope the algorithm smiles on you. If you can’t make fire on your own, the industry rarely stops to offer you flint and kindling. Artist development was once a core function of record labels but from the outside, it now feels like a luxury reserved for a few outliers. [Today, I see a few exceptions. Doechii and Tyla seem to have terrific teams playing a long game with their career arcs.]

Will they go extinct?

There are recent efforts to establish group acts that are worth noting. The British trio FLO styles itself after '90s R&B girl groups, and watching them perform is thrilling. They are vocally tight, visually cohesive, and clearly trained. They harmonize and move like they study their predecessors. But can they survive in an industry that no longer knows how to nurture what they're offering?

Chloe and Halle Bailey, who came up under Beyoncé's Parkwood Entertainment label, are perhaps the most promising American act of the last decade to embody the spirit of the group. Their trajectory was building beautifully until the pandemic pulled the brakes on their momentum. But the sisters remain under contract for more albums. I believe their story isn't finished yet.

Then there's K-pop, where groups remain the centerpiece. These groups are often the product of years of bootcamp-style development—a model that borrows heavily from the Black American artist development lineage and then multiplies its discipline by ten. Training starts young. Every member of the group becomes a skilled dancer, vocalist, and has a well-designed personality. Their role in the group is predetermined and mastered over years before we, the public, meet them. The intensity borders on exploitation, transforming children into products with a ruthlessness that makes even the old American system look gentle by comparison. (The K-pop methods are documented in Netflix's reality competition show "Pop Star Academy.")

Recently, Def Jam introduced a new boy band called 2BYG, rooted in the nostalgia of New Jack Swing. Their debut video, Karma, has all the right ingredients: coordinated choreography, nostalgic styling, and an obvious reverence for what came before. It feels like possibility. DefJam is betting on them. Banking on the idea that maybe that this form isn't entirely gone.

Betting on magic in a world that's forgotten how to believe in it means you might lose. The industry that devoured TLC's dreams is still here, still hungry. The algorithms that reward viral moments over lasting artistry are still running the show. If we allow the logic of profit to become the only driver of what gets made, we sacrifice our need to create and our craving for beauty.

So I'll keep watching. Keep listening. Keep buying tickets when I can. Let’s hope that somewhere in a garage or a church basement or a living room, five kids are practicing harmonies they heard on their parent’s playlists, learning choreography from YouTube videos, molding themselves into a unit. When they arrive, let’s help them make it.

The Netflix docuseries “Dirty Pop” shows Pearlman creating Backstreet Boys and SYNC. It’s a sad story of corruption and adults taking advantage of child stars.

One day when I learn to sing 5 vocal lines at once, I’m gonna show up to someone’s karaoke night and kill a performance of New Edition’s “Can You Stand the Rain.”

I thought your analysis on the church as a site of artistic development was really excellent — and made clear that I haven’t heard you singly nearly enough!! (though you’ll belt a lovely line or two from time to time).

Why do you think there are some teams / labels still willing to bet on magic (your examples of Doechii, Tyla, 2BYG, etc)? Do you think that’s more the label, or the force of personality of an artist like Doechii?

I really enjoyed reading. I have been wondering the same thing and this provided answers.